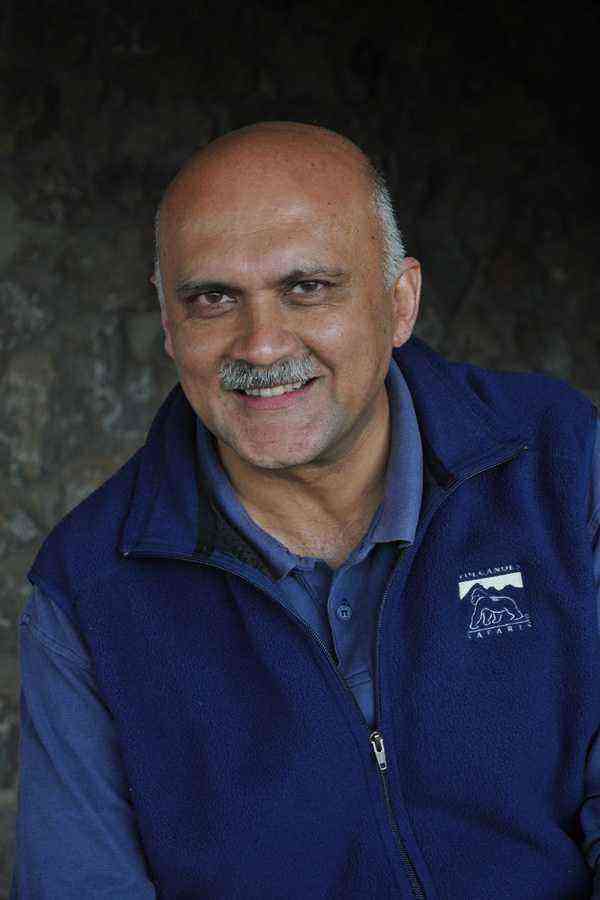

Moman’s family left for the UK in the 1970s, and after the expulsion of Asians and Europeans from Uganda turned members of his family into refugees, Moman thought he’d lose his connection to Africa forever. But later in life, his work for the European Union in Brussels brought him back to Southern and Eastern Africa. With the area in flux post-conflict, Moman had an immense warmth for his first home, and his relationship with the region was rekindled.

“For me it’s been very important to balance what you build, with the connection to conservation and communities, and to try to keep what you have as simple as possible.”

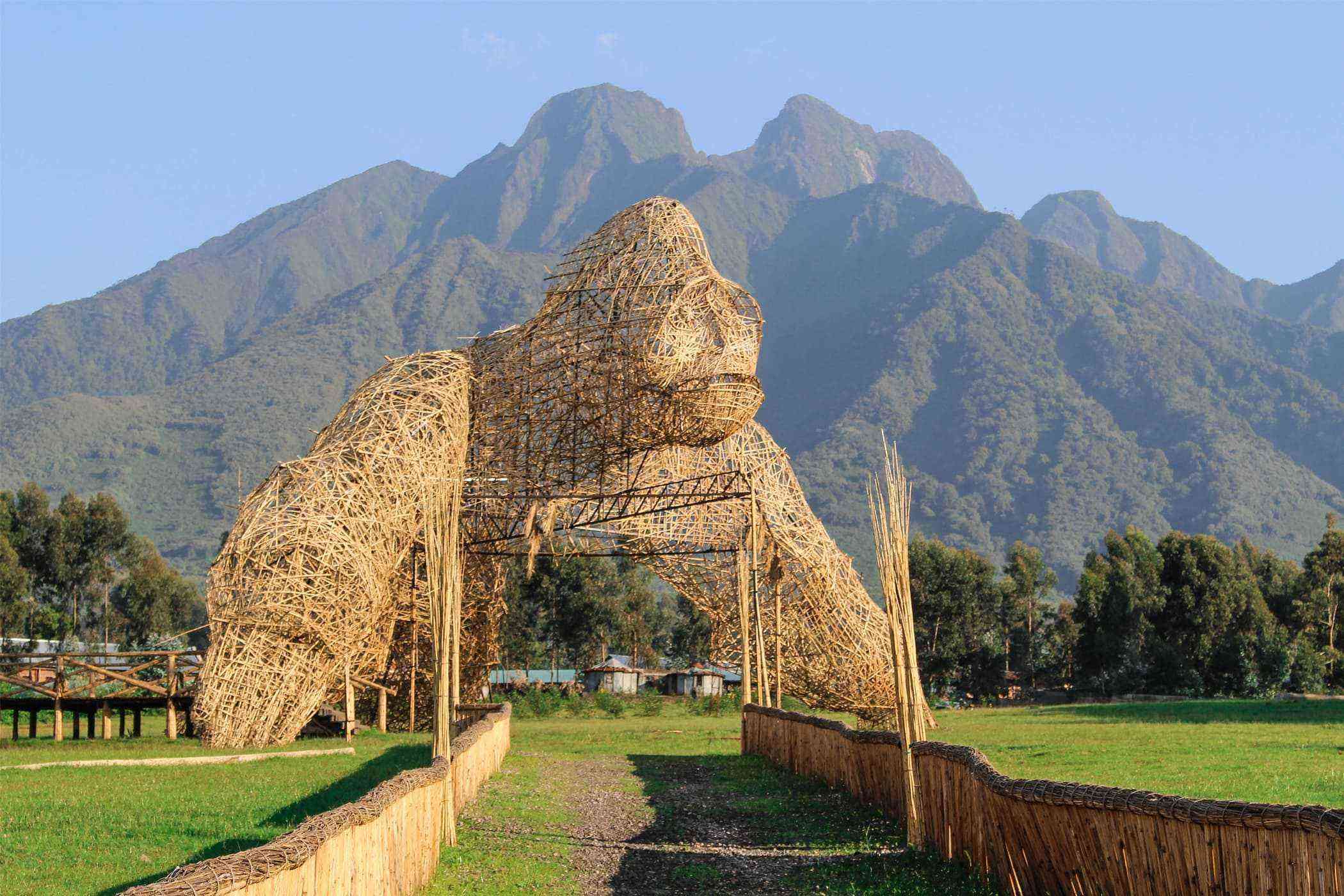

After working for the British government in London in 1997, Moman founded Volcanoes Safaris to conscientiously revive tourism in and around the Western Rift Valley, home to a population of gorillas and chimpanzees, and to give visitors an opportunity to engage with the endangered wildlife. In 2004, his company built the Virunga Lodge, a luxury lodge overlooking the Virunga volcanoes, which straddle Rwanda, Uganda, and the DRC, providing visitors with a luxury experience and a way to give back to the region. In addition to their flagship property in Rwanda, Volcanoes Safaris owns three properties in Uganda: one in Mount Gahinga, one further north in Bwindi, and the Kyambura Gorge Lodge in Uganda (the Contemporary Chimp and Wildlife Lodge).

We spoke with Moman about finding a balance between luxury tourism and his commitment to preserving the region and its wildlife.

What was it like when you returned to Uganda for the first time?

In 1970 when I left [Uganda], it was eight years after [the country gained] independence. There had been political changes and tensions about what to do about the fact that the economy was still owned in East Africa largely by non-black people, even though they had independence. But the country of Uganda was functioning really well. They had a really good economy, a really good education system for the black population, one of the most forward thinking and educated in East Africa, and the best university in Africa. One minute you’re working in a functioning state, whatever its complexities and negative issues, and the next minute you suddenly get a dictator who takes over, and then of course of the country collapses.

So really from the moment I left—you can blame it all on me [laughs]—the country collapsed. In 1982 the peace and security in the city of Kampala was destroyed. I drove back from Nairobi in a European Union car, there were roadblocks and drunken soldiers and the feeling of a culture not at peace, a curfew, and gunshots at night. The population of people who had lived there before, a good chunk of them Indians and Europeans, were no longer there, and there were people illegally occupying the city. It was a major change. Instability continued for several years. And in 1986 Museveni took over, and a good 20 years after I left I was able to travel the country normally, and climb the Rwenzori mountains and rediscover the West. It didn’t go back to these glories days of this wonderful country in the ‘60s and ‘70s, but it did stabilize again—but that’s what kept my interest alive.

What initially inspired you to start Volcanoes Safari?

When I first went to the Ugandan side of Virungas in the ‘60s, it was actually roughly the same time that Dian Fossey [whose work was fundamental in understanding gorillas and how to protect them] was setting up in the area, so though I never met her, I heard about what one might call this ‘crazy American woman’ who had been working with the gorillas on the other side of the volcanoes. It’s a distant memory I have of this person, and she was an inspiration to me. I was [also] inspired by Walter Baumgärtel’s early efforts with gorilla tourism in the Gahinga side of the Virunga Volcanoes.

Do you ever feel conflicted about establishing luxurious lodgings in a region that’s endured so much hardship?

For me it’s been very important to balance what you build, with the connection to conservation and communities, and to try to keep what you have as simple as possible. Many of clients are really, really wealthy, and they are used to a fairly high standard of basic amenities. To meet their requirements we’ve become a much more luxurious company, but our origins and our ethos and our thinking still remain very connected to the region where we are. We employ over 100 staff members in this area of southern Uganda, and all of our staff come from Rwanda, DRC, Burundi, Uganda, and Kenya. They have been through conflict; they have suffered as refugees, they have suffered from trauma—issues that parallel my own family’s. We must keep giving back to the community.

What do you tell people who still have misconceptions about the region?

The Rwandan genocide was one of the most negative episodes of the 20th century so understandably there’s fear about it, there’s concern about it. As a tourism provider, you have to decide if the region is safe and secure enough for tourists. Tourism can play a very important part both in terms of finance and in perception and psychology. So the old question, ‘does tourism bring peace or does peace bring tourism?’ comes into play.

“It’s one of the most fertile areas in Africa. It’s a rural paradise.

There are moments when you can’t really work in a place in a particular country because things are too unstable, and there are moments when it starts changing, and then you can help that process. As it happens in Uganda and Rwanda, we did ride the early wave of uncertainty, but it has sustainable peace, and the government has taken control of the area. There’s been the odd incident or negative news from the DRC, but our clients have remained safe and felt safe, so sometimes the negative perception is no longer valid. Rwanda today for a client is one of the safest countries in the world. I can say that having been back and forth and living there part of the year since 2000. You can walk the streets at night and you can drive everywhere, because security has been achieved. That wasn’t the case 15 years ago.

How can guests give back to the community during their stay at the lodges?

Clients can purchase water tanks to give to locals, and for about $40 you can buy and donate a sheep to a family; the sheep helps produce manure to create better soil for guests, and it becomes a whole regeneration project.

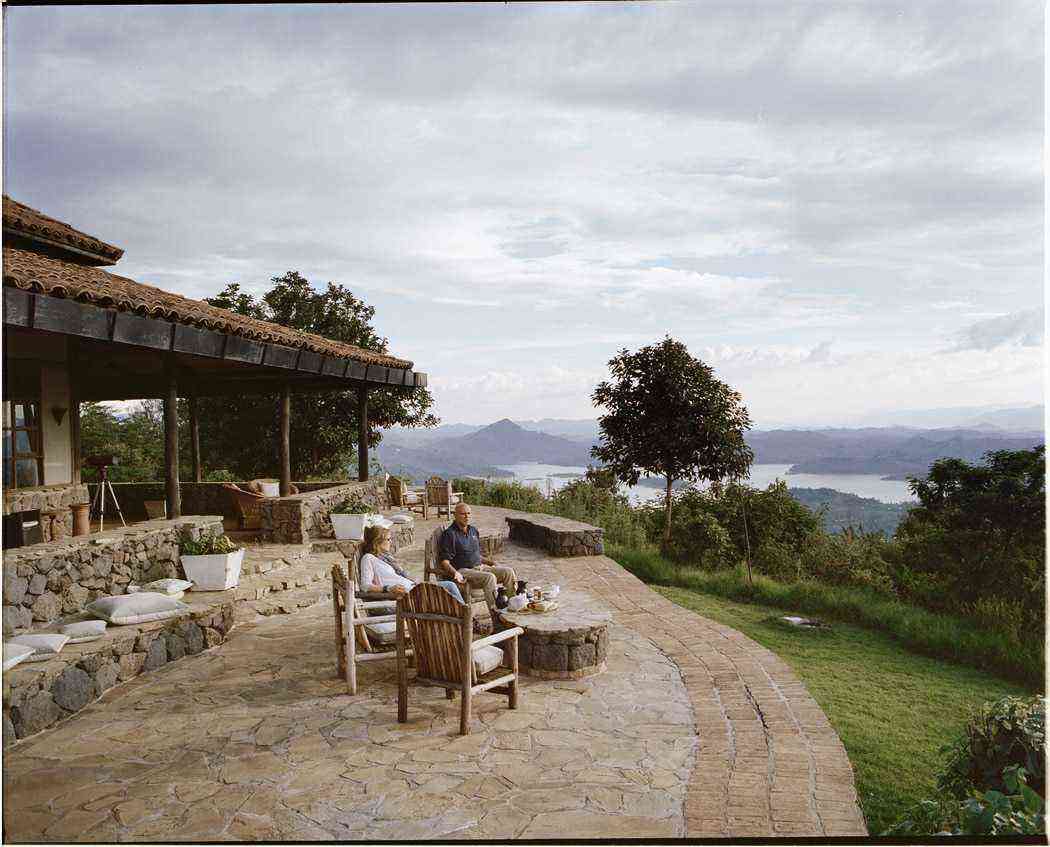

What do you see when you look out from the terrace of the Virunga lodge?

The Virunga volcanoes at the source have these eight volcanoes that are still live on the Congo side, and then the ones in Uganda that are not, and that’s where the gorillas live. And then there are all these foothills…It’s a very intense area because the volcanos are very beautiful. The parkland around them is quite small. There’s cultivation all around; it’s one of the most fertile areas in Africa. It’s a rural paradise. You see these dramatic views of the volcanoes; you see about five of them from the Virunga lodge. And from the Ugandan side, from Gahinga, you’re in a kind of in a bowl at the base of three of them. From the Virunga Lodge, the views are very widespread over the valley, and these two shimmering lakes of Buerera and Ruhondo, and these small homesteads dotted around where people are trying to make a living. In the forest you have these gorillas which number about 880; it’s a very precarious population. It’s one of the most unusual locations in the world. It’s very special geographically, historically, ethnically, politically, and linguistically around the volcanoes.

Learn more about Praveen Moman in Sophy Robert’s photo essay, Into the Virungas with photos by Michael Turek, and visit the Volcanoes Safaris website to learn about how you can visit the lodges and participate in wildlife safaris. Newly opened at the Virunga lodge is the Dian Fossey map room in memory of Fossey and other explorers who helped connect the region to the world.

| August 21, 2017